Today is Memorial Day, an American holiday observed on the last Monday of May that honors men and women who died while serving in the U.S. military. Originally known as Decoration Day, it originated in the years following the Civil War and became an official federal holiday in 1971. Many Americans observe Memorial Day by visiting cemeteries or memorials, holding family gatherings and participating in parades. Unofficially, at least, it marks the beginning of summer.

According to the U.S. Army Military History Institute, iCasualties.org, and Wikipedia, in this country’s first 100 years of existence, over 683,000 Americans lost their lives, with the Civil War accounting for 623,026 of that total (91.2%). Comparatively, in the next 100 years of America as a recognized nation, a further 626,000 Americans died through two World Wars and several more regional conflicts (World War II representing 65% of that total). Using this comparison, the Civil War might very well be the most costly war that America has ever fought.

To date, American soldiers—men and women—have served and fought in 35 wars, including the Afghanistan War which is still ongoing. Also ongoing is a “war on terrorism,” a war without borders, a war without clearly identifiable enemy uniforms.

To date, American soldiers—men and women—have served and fought in 35 wars, including the Afghanistan War which is still ongoing. Also ongoing is a “war on terrorism,” a war without borders, a war without clearly identifiable enemy uniforms.

Memorial Day is a day of remembrance for those who have put on the uniform—whether Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine or Coast Guard—to serve in the defense of this country and made what is commonly referred to as the ultimate sacrifice.

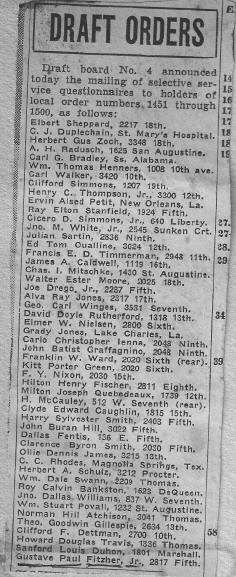

The Draft

A lot has changed, however, with regard to this country’s attitude towards the military in the last few decades. I write of this from personal experience. Two weeks after graduating from what is now Herbert Lehman College in the Bronx in 1966, I received a letter from the United States government that began with the words: “Greetings.” It was a draft notice. A couple of weeks later I was standing stark naked somewhere in lower Manhattan with what seemed like at least a hundred other young men for a line-up physical exam. In a Neil Simon comedy about the military this would have been humorous. As one person among this throng, I was not amused.

A lot has changed, however, with regard to this country’s attitude towards the military in the last few decades. I write of this from personal experience. Two weeks after graduating from what is now Herbert Lehman College in the Bronx in 1966, I received a letter from the United States government that began with the words: “Greetings.” It was a draft notice. A couple of weeks later I was standing stark naked somewhere in lower Manhattan with what seemed like at least a hundred other young men for a line-up physical exam. In a Neil Simon comedy about the military this would have been humorous. As one person among this throng, I was not amused.

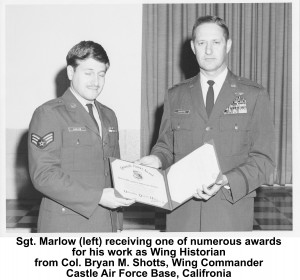

To cut a longer story short, in June 1966 I volunteered for the United States Air Force, a hitch that lasted four years, as opposed to the two years I would have served in the United States Army. Frankly, it was a survival strategy. I gave two more years of my life to the United States military rather than risking losing my life in the jungles of Viet Nam. Looking back on this strategic decision I have mixed emotions.

On the one hand, I avoided the high chance of having an M-16 put in my hand and serving in a forward area somewhere in Vietnam, Laos, or Cambodia. I was not a conscientious objector, but I also did not relish the idea of having to kill someone for either military tactical purposes of self-survival. To a degree, I still wrestle with the moral consequence of this decision. I also wonder what experiences I might have had if I had gone along with the government’s wishes—which I did not. I decided to keep as much control of my life as I could, even though it meant two more years working for Uncle Sam.

On the other hand, I traveled half way around the world to Guam in the South Pacific for a time courtesy of the U.S. government. Anderson Air Force Base on Guam is not Hawaii or Bali, but while there I experienced another part of the planet and grew as a writer—I was on temporary assignment from my position as a wing historian at Castle Air Force Base in Merced, California. Castle was the long-time training base for all of Strategic Air Command. I was assigned to the historian section on Guam. There I was supervised by a civilian, one Dr. Kritt, who taught me a thing or two about historical writing. We also played poker (every Saturday night).

On the other hand, I traveled half way around the world to Guam in the South Pacific for a time courtesy of the U.S. government. Anderson Air Force Base on Guam is not Hawaii or Bali, but while there I experienced another part of the planet and grew as a writer—I was on temporary assignment from my position as a wing historian at Castle Air Force Base in Merced, California. Castle was the long-time training base for all of Strategic Air Command. I was assigned to the historian section on Guam. There I was supervised by a civilian, one Dr. Kritt, who taught me a thing or two about historical writing. We also played poker (every Saturday night).

The four year experience—that took me from New York City, to Texas, Illinois, California, and Guam and back to California again—was a maturing period. It also gave me the GI Bill. Those funds gave me the opportunity to earn an MBA (general management), then a Ph.D. (media studies). Those degrees gave me the credentials to become a college professor. I was honorably discharged in June 1970 and remained on inactive reserves until 1972.

In 1973 the United States congress did away with the draft. The draft, or conscription as it is also called, in the United States has been employed several times, usually during war but also during the nominal peace of the Cold War. When the United States discontinued the draft it moved to an all-volunteer military force, thus there is currently no mandatory conscription in effect. Not many people know this, or want to know this, but the Selective Service System remains in place as a contingency plan; men between the ages of 18 and 25 are required to register so that a draft can be readily resumed if needed. In current conditions conscription is considered unlikely by most political and military experts.

The elimination of the draft in 1973 was in some ways a relief to many parents and young men between the ages 18-25. Many years later, in 1986 I became the proud father of fraternal twin sons. Today they are 27 years old and I don’t fret about the possibility of their having to serve in the military. But I also have mixed feelings about this.

While I was in the Air Force I met people from all over the United States and some from other parts of the world—the government didn’t care if you were born here or not; if you were in this country and of the proper age, regardless of citizenship, you were eligible for the draft. These folks were of varying degrees of ethnicity, cultural and religious background, and educational attainment. The variety of human beings from slick sleeve privates to four star generals was reflective of the American melting pot. In a very positive sense, the draft brought a serendipitous mix of young men together in one place at one time, and the mixing up of these cultures provided a healthy shot in the arm to the usually perceived military credo of rank and file, hierarchy, and groupness. It was an education in itself. I learned more about organizational communications and structure from my four years in the military than at any time.

While I was in the Air Force I met people from all over the United States and some from other parts of the world—the government didn’t care if you were born here or not; if you were in this country and of the proper age, regardless of citizenship, you were eligible for the draft. These folks were of varying degrees of ethnicity, cultural and religious background, and educational attainment. The variety of human beings from slick sleeve privates to four star generals was reflective of the American melting pot. In a very positive sense, the draft brought a serendipitous mix of young men together in one place at one time, and the mixing up of these cultures provided a healthy shot in the arm to the usually perceived military credo of rank and file, hierarchy, and groupness. It was an education in itself. I learned more about organizational communications and structure from my four years in the military than at any time.

I keep wondering if the elimination of the draft and the creation of an all-volunteer military has in a way damaged what used to be a healthy heterogeneous experience into one that promotes homogeneity to the military’s own detriment. It’s doubtful that graduate degreed individuals are attracted to serve in the military in the non-officer ranks. As a commissioned officer, perhaps yes, but not as non-commissioned officer (aka: non-com). Is there a  danger in the loss of a heterogeneous military? I’m not certain, but a volunteer military is going to attract a certain kind of individual, with a certain level of education and cultural background. To put this in biological terms, the elimination of the draft limits the gene pool that was richer personnel-wise prior to 1973.

danger in the loss of a heterogeneous military? I’m not certain, but a volunteer military is going to attract a certain kind of individual, with a certain level of education and cultural background. To put this in biological terms, the elimination of the draft limits the gene pool that was richer personnel-wise prior to 1973.

There’s another unintended consequence: the elimination of the draft diminished the concept of community service on a national scale. When veterans returned from World War II there was a sense of community and civic engagement among these veterans that could not be duplicated artificially. The shared military experience created a bond even among the many who did not serve in the same place or time. The shared military experience creates a sense of community and understanding that is unique.

For those who work with the many who have never served in the military or who have never put on a uniform of any kind, it can be a frustrating experience. When I returned to New York City after having completed my four-year commitment the reception I received was no reception at all. No one wanted to know or cared about the military experience I had successfully completed. When I went for job interviews the military experience on my resume was not valued or appreciated and was altogether dismissed.

Today, returning veterans from the Iraqi and Afghanistan wars are getting much better treatment, but the governmental support for these veterans in terms of easing them back into civilian society is nominal when it should be a higher priority.

Today, returning veterans from the Iraqi and Afghanistan wars are getting much better treatment, but the governmental support for these veterans in terms of easing them back into civilian society is nominal when it should be a higher priority.

Those who have never put on a uniform or carried a gun—I was an expert marksman with an M-16—just don’t understand. It’s beyond their experience. It’s outside their need to want to know. Memorial Day should be a day for reaching out—not only to remember those who have died, but also to those who have served and are still working at taking the uniform off.

Please write to me at meiienterprises@aol.com if you have any comments on this or any other of my blogs.

Eugene Marlow, Ph.D.

May 27, 2013

© Eugene Marlow 2013