The Aspen Music Festival and School, one of the premiere classical music festivals and summer music camps in the United States, if not globally, has a multi-year history of selecting and working with a handful of young emerging composers. This summer the “composition program” tried something different with its “Composition Showcase.”

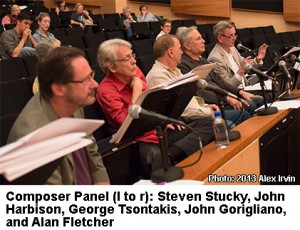

The school put together a veritable gathering of mainstream classical music eagles: Steven Stucky, John Gorigliano, John Harbison, and George Tsontakis. Robert Spano, Music Director, and Alan Fletcher, President and CEO, were also on hand for the 9 a.m. event at Harris Hall, the Aspen Music Festival’s year-round concert venue. On the stage was the American Academy of Conducting Orchestra, plus several of the conductors in the program innovated by the Aspen Music Festival.

Just look at this roster, particularly the first four names—Oscars, Pulitzer Prizes, Kennedy Center Friedheim Awards, American Academy of Arts and Letters Lifetime Achievement Award, Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition, Charles Ives Living Award, plus the accomplishments of Spano and Fletcher. You could not have a more highly qualified group of composers commenting on the student composers’ evolving orchestral works.

Just look at this roster, particularly the first four names—Oscars, Pulitzer Prizes, Kennedy Center Friedheim Awards, American Academy of Arts and Letters Lifetime Achievement Award, Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition, Charles Ives Living Award, plus the accomplishments of Spano and Fletcher. You could not have a more highly qualified group of composers commenting on the student composers’ evolving orchestral works.

And what an opportunity for the composers. Throughout the double four-week season they work with the senior composers and then get to listen to their symphonic creations performed by the real thing. At the August 11 showcase, the composers had a section of their work performed, followed by a critique by the gathered senior composers. This observer was impressed not only by the quality of the evolving compositions, but also by the measured, insightful quality comments by the gathered award-winning senior composers.

Following the playing of the composition excerpts, the orchestral players vacated the stage in preparation for a conversation among the composers, junior and senior, and members of the audience who turned up for the Sunday morning event. Lasting over an hour, the conversation quickly turned to the subject of audience.

John Corigliano, whose credentials as a world-class mainstream classical composer give him much credibility, made the following point, and I paraphrase: “Before each performance, the composer of the new piece should get up in front of the audience and explain the nature of the piece. In this way, the audience will have a better understanding of the piece and presumably a better appreciation of the work.”

John Corigliano, whose credentials as a world-class mainstream classical composer give him much credibility, made the following point, and I paraphrase: “Before each performance, the composer of the new piece should get up in front of the audience and explain the nature of the piece. In this way, the audience will have a better understanding of the piece and presumably a better appreciation of the work.”

This comment speaks to what a lot of audience members, in particular, have referred to, and it is nothing new. Many audiences are reluctant to attend a classical music concert, in particular a new music classical concert, for fear they will not understand what they hear. This is apparently true since the emergence of serial music earlier in the 20th century. Audiences would rather listen to the “traditional classical repertoire.” At least then they feel a lot less intimidated. And there are plenty of ensembles and orchestras willing to accommodate the audience in this way.

Yet, the history of music, just like the history of everything else, is not static. The 20th century saw the advent of jazz in a variety of music styles as it advanced through the century. Same with classical music in its move away from the Romantic music of the Victorian era. Same with popular music: from ragtime to swing, to rock ‘n roll and country and western, to acid rock and grunge, and rap and hip-hop. And as Burton W. Peretti, author of Jazz in American Culture (The American Ways series, 1997), points out in numerous chapters, new music is usually the thrust of young musicians and audiences. Therefore, does it not stand to reason that with each new generation, the music of the older generation moves out of the spotlight to make way (reluctantly) to the new music of the younger generation.

Yet, the history of music, just like the history of everything else, is not static. The 20th century saw the advent of jazz in a variety of music styles as it advanced through the century. Same with classical music in its move away from the Romantic music of the Victorian era. Same with popular music: from ragtime to swing, to rock ‘n roll and country and western, to acid rock and grunge, and rap and hip-hop. And as Burton W. Peretti, author of Jazz in American Culture (The American Ways series, 1997), points out in numerous chapters, new music is usually the thrust of young musicians and audiences. Therefore, does it not stand to reason that with each new generation, the music of the older generation moves out of the spotlight to make way (reluctantly) to the new music of the younger generation.

But it not just an issue of one generation or another. If it were, we would not still be appreciating and listening to the music of the Renaissance, the Baroque period, the classical period, the Romantic period or the 20th century, such as Gilbert and Sullivan, Irving Berlin, Rodgers and Hammerstein (essentially songs from the Great American Songbook), or Leonard Bernstein, the Beatles, or Michael Jackson.

The aforementioned Dr. Peretti—Acting Dean of the Graduate School and Continuing Education, and a Professor in the Department of History and Non-Western Cultures at  Western Connecticut State University—in the “Epilogue” chapter of his aforementioned book, makes the following commentary:

Western Connecticut State University—in the “Epilogue” chapter of his aforementioned book, makes the following commentary:

. . .the jazz story raises some interesting questions about the role of the arts in recent history. As jazz musicians became more accomplished and began to create for themselves—rather than to satisfy audiences tastes—did they become irresponsible “elitists”? Should performers originally nurtured by the people continue to serve the people? Stan Kenton, the “progressive” jazz bandleader, thought he was doing so, though many jazz fans rejected him. The players active in 1960s black communities tried to connect with average listeners by playing simple melodies and incorporating soul and funk elements into their sounds, but their complex styles kept them from gaining wide followings.

So if it is not totally a matter of one generation or another, what is it then? Dr. Peretti seems to conclude that jazzers, for example, lost their audience because the music was too complex, unlike the simpler and accessible and “danceable” melodies of the swing era. Bebop, of course, took jazz on a right turn and jazz became complex listening music. This is perhaps an over-simplification—there are many factors, including aesthetic ones that re-shape an art. But it is still true. And when you have the likes of trumpeter Miles Davis literally turning his back on the audience during a performance, or in more contemporary times, trumpet virtuoso Dave Douglas not even talking to the audience during a set, you get an audience turned off by the performance.

Which is why Corigliono’s comment noted earlier is so very apt. Despite the observable behavior of many people, especially young people, apparently buried in their mobile and desktop electronic screens when sitting, walking, even talking, people crave for connection. This is perhaps a central reason why the current repertoire of pop music—over-simplistic, melodically repetitive music, basically driven by a drum rhythm—is so popular. It is very accessible. People don’t have to think too hard (if at all) about what they hear. But it is also not very uplifting or challenging. It is music for the moment, not music to  be cherished for later listening. It is highly transitory, manufactured, and replaceable.

be cherished for later listening. It is highly transitory, manufactured, and replaceable.

What is needed is music that connects with an audience, that draws an audience in and takes them on a journey, music that transcends the outside world and takes an audience to another level. This music doesn’t have to be complex, or blip-blop, or esoteric, or designed to impress other composers or performers. Music is about emotions, that is, connecting with an audience on some emotional level. Ironically, to create this music requires creativity and intellect, but that doesn’t mean the music is constructed on an intellectual basis. That kind of music is an exercise. Music that reaches people is music that comes from the heart.

Please write to me at meiienterprises@aol.com if you have any comments on this or any other of my blogs.

Eugene Marlow, Ph.D.

September 9, 2013

© Eugene Marlow 2013