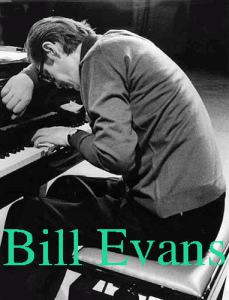

William John Evans, known as Bill Evans (August 16, 1929 – September 15, 1980), was an American jazz pianist and composer who mostly worked in a trio setting. He is widely considered to be one of the greatest jazz pianists of all time, and is considered by some to have been the most influential post-World War II jazz pianist. Evans’s use of impressionist harmony, inventive interpretation of traditional jazz repertoire, block chords, and trademark rhythmically independent, “singing” melodic lines continue to influence jazz pianists today. Unlike many other jazz musicians of his time, Evans never embraced new movements like jazz fusion or free jazz.

Despite his success as a jazz artist, Evans suffered personal loss and struggled with drug abuse. Both his girlfriend Ellaine and his brother Harry committed suicide, and he was a long time user of heroin, and later of cocaine. As a result, his financial stability, personal relationships and musical creativity suffered until his death, in 1980.

Many of his compositions, such as “Waltz for Debby,” have become standards and have been played and recorded by many artists. Evans was honored with 31 Grammy nominations and seven awards, and was inducted in the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame.

The abovementioned history is drawn from “official” recollections of his life. What follows is my personal recollection of Bill Evans, mostly because for a time I lived next door to him.

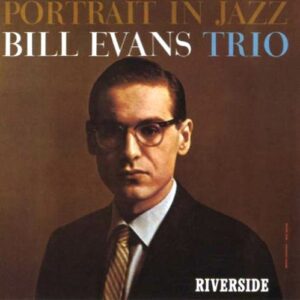

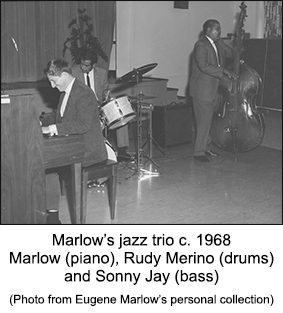

When I was in California—courtesy of the United States Air Force, 1966-1970; for most of the time I was a wing historian at Castle Air Force Base in Merced, California—I had the opportunity to form a standard jazz trio and for a time a quartet (piano, bass, drums, and vibraphone). During this sojourn in the San Joaquin Valley much of our musician talk was about Bill Evans who, in retrospect, was in the heart of his career. I had a couple of his albums. His playing was sublime. I endeavored and succeeded in a very small way to imitate his playing and approach.

When I was in California—courtesy of the United States Air Force, 1966-1970; for most of the time I was a wing historian at Castle Air Force Base in Merced, California—I had the opportunity to form a standard jazz trio and for a time a quartet (piano, bass, drums, and vibraphone). During this sojourn in the San Joaquin Valley much of our musician talk was about Bill Evans who, in retrospect, was in the heart of his career. I had a couple of his albums. His playing was sublime. I endeavored and succeeded in a very small way to imitate his playing and approach.

I returned to New York in September 1971 and moved into a studio apartment in Riverdale, New York, on the west side of the Bronx. My worldly goods at the time included a pretty beat up baby grand that I had shipped from California. This was my main piece of furniture, together with a half dozen boxes of clothes, books, music, and other papers. The movers brought in the goods in early evening, including the piano.

The door to my apartment was slightly ajar that evening—it was quite hot as I recall—when all of a sudden two Siamese cats wandered into my yet unorganized space. I was somewhat surprised, but as I am a long time cat lover, I was somewhat bemused. I presumed they belonged to someone on the floor. A few moments later, a woman in her forties, dressed (almost) in a negligee and nightgown knocks on the door and comes in. She says “I’m sorry. My cats must have wandered from the hall into your apartment.” She then spies the piano and asks “Are you a pianist?” I answered “Yes, I play jazz.” She  responded “My husband is also a jazz pianist.” We chatted for a few more minutes when I indicated I had just moved in and was, frankly, tired. She left shortly afterwards. I hoped I hadn’t been too rude, but I was, indeed, quite exhausted from the move in. I also didn’t think much more of her comment that her husband “was also a jazz pianist.”

responded “My husband is also a jazz pianist.” We chatted for a few more minutes when I indicated I had just moved in and was, frankly, tired. She left shortly afterwards. I hoped I hadn’t been too rude, but I was, indeed, quite exhausted from the move in. I also didn’t think much more of her comment that her husband “was also a jazz pianist.”

About three weeks later I was leaving my apartment in the early evening to go somewhere, I don’t remember where, when, as I was halfway down the hall to the elevator, the door next to my apartment opens and a tall, greying-haired man comes out and kisses the woman I had met three weeks earlier. I thought to myself, “Gene, turn around and greet your next door neighbor.” As I walked towards him and him towards me, I began to develop a feeling of realization. A few more steps and we were face-to-face with each other. He extended his hand and as I reciprocated in kind he said “Hi, I’m Bill Evans.” Like a teenage groupie who had never met a celebrity before, I answered “The Bill Evans?” His response was a smile and a “Yes.” We chatted for a moment and went down the elevator together. He to his car, me to I frankly don’t remember. I was in shock and awe. As we parted I think he invited me to where he was playing, The Village Gate, and mentioned the name of his agent, Helen Keane.

A week or so later, I went to the club, met Helen Keane, and sat for a couple of hours in complete ecstasy while I listened to and watched Evans play. His hands were huge, somewhat puffy, more like a stevedore than a pianist—perhaps as a result of the drug lifestyle. More than likely this was his inherent physical being enhanced by his past training. He once told me: “I just worked harder than anybody else.”

I was quite frankly intimidated. When I realized I had been playing my piano while one of the world’s greatest jazz musicians was probably listening next door in his kitchen adjacent to my space or perhaps in his living room, I virtually stopped playing—for about five years actually. How I recovered from this paralysis is another story.

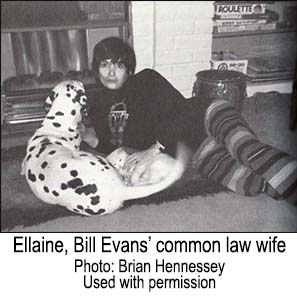

Entering Bill’s apartment was akin to entering sacred ground—or that’s how it felt to me at the time. I became quite friendly with Ellaine Evans, his common law wife—they had been together for more than seven years. I would come over from time to time and play chess with her. She was quite good at the game and delighted in beating me. Meanwhile, Bill was in the bedroom resting. He was not to be disturbed for any reason.

On occasion Bill would come over to my place and we would chat. Once I asked him if he would give me a few lessons. His answer was “You know what your problems are.” It was a harsh response and at the time I thought very ungenerous, but he was also right. I knew what my problems were, but at the time I was looking for a father figure to give me the push I was yearning for to raise my musical game. That person came into my life in 1980, the same year Bill died, in the form of Dr. Billy Taylor.

One Christmas eve I was invited over to Bill and Ellaine’s place for a party. His drummer at the time Marty Morell and his bass player, the great Puerto Rican bassist Eddie Gomez and his spouse, were there. It was a strange episode. They were the only people there and me. Even though the players had worked together for some time, there wasn’t much conversation. I don’t even remember if I said anything, other than cordial greetings with Morell and Gomez. The apartment was dimly lit, almost surrealistic. It was a very uncomfortable setting and feeling. I think I had something to drink and left after about 30 minutes without saying much or having much said to me.

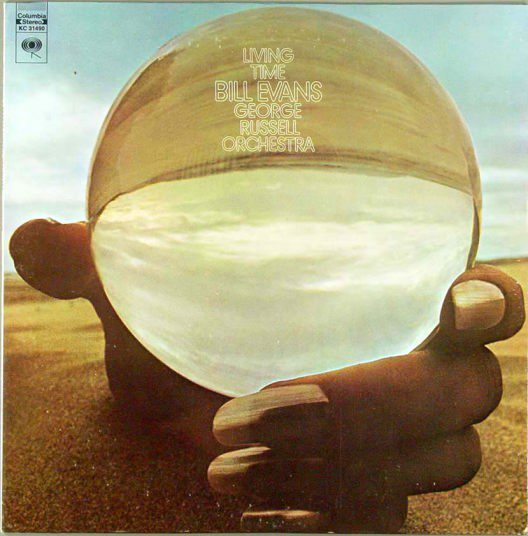

My next door neighbor circumstance also resulted in an invitation to attend a playback session at Columbia Records of the newly recorded “Living Time” by George Russell with Evans at the piano. This large scale piece full of cross meter sections and improvisations was commissioned by Evans. I was honored to be in the same studio with a host of glitterati from the jazz world. But other than Bill and Ellaine, I had no idea who I was sitting next to or who else was in the room.

My next door neighbor circumstance also resulted in an invitation to attend a playback session at Columbia Records of the newly recorded “Living Time” by George Russell with Evans at the piano. This large scale piece full of cross meter sections and improvisations was commissioned by Evans. I was honored to be in the same studio with a host of glitterati from the jazz world. But other than Bill and Ellaine, I had no idea who I was sitting next to or who else was in the room.

I was closer to Ellaine than Bill. He was an ex-druggie, owed money to the IRS, and was on methadone. Actually, the two of them were on methadone: Ellaine had gone on drugs just so she could be with Bill in his world.

When they went on tour, I would take care of their Siamese cats: Melanie and Lita. Neither was spayed, so at night the two would make a hell of a racket, causing me to lose sleep. But these were Bill’s cats, and therefore it was an honor. As it turned out I inherited these cats after Ellaine committed suicide. Melanie, the larger of the two died in a veterinarian’s office while ill. I think she was very scared and must have thought she had been abandoned. The smaller of the two, Lita, was actually the stronger. She died many years later at the ripe old cat age of 23!

The year before Ellaine killed herself, Bill’s brother Harry committed suicide and it is reported this deeply affected Bill’s demeanor and outlook. This personal family tragedy was exacerbated when Bill went on tour to Japan with Ellaine and then back to California. She returned to New York without him. A couple of weeks later Bill turned up with what my girlfriend at the time—a very bright woman who lived directly across the hall from me—described as a “California cookie,” knocks on his apartment door, and announces to Ellaine, “I want us all to be friends.” About 10 days later Ellaine dressed herself in one of Bill’s favorite outfits and jumped in front of an A train at the 96th Street station.

I attended the memorial service. Contrary to the Christmas party, Marty Morell appeared very involved, while Eddie Gomez seemed more concerned about where the next gig was going to be.

Bill seemed devastated. I heard him play at a New York City summer jazz festival at Carnegie Hall a couple of years later. His playing was not the same. Perhaps I was projecting, but I perceived the soul had gone out of him.

He and Nenette, his California cookie—actually she was Canadian—moved to Fort Lee, New Jersey, and had a son, Evan Evans, whom I met many years later at a jazz convention in New York City. If I recall correctly, he was also a pianist, and was attempting to purvey a documentary about his father’s life.

On September 15, 1980, Evans, who had been in bed for several days with stomach pains at his home in Fort Lee, was accompanied by jazz drummer and composer Joe LaBarbera and his wife Laurie Verchomin to the Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, where he died that afternoon. The reported cause of death was a combination of peptic ulcer, cirrhosis, bronchial pneumonia, and untreated hepatitis. Evans’s friend, Canadian music critic and biographer, Gene Lees described Evans’s struggle with drugs as “the longest suicide in history.” He was interred in Baton Rouge, next to his brother Harry.

On September 15, 1980, Evans, who had been in bed for several days with stomach pains at his home in Fort Lee, was accompanied by jazz drummer and composer Joe LaBarbera and his wife Laurie Verchomin to the Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, where he died that afternoon. The reported cause of death was a combination of peptic ulcer, cirrhosis, bronchial pneumonia, and untreated hepatitis. Evans’s friend, Canadian music critic and biographer, Gene Lees described Evans’s struggle with drugs as “the longest suicide in history.” He was interred in Baton Rouge, next to his brother Harry.

It was a sad moment for many. But when my composition teacher at the time, Harold Danko, informed me of Evans’s passing, I had mixed feelings. I thought more of Ellaine who had supported Bill in so many ways. I thought of the cats now living with me who would be a constant connection to my brief, but not deep relationship with one of the world’s greatest jazz pianists of the trio genre.

I think now of the inherent contradiction: Bill’s great jazz conceptualizations, on the one hand, and the self-destructive tendencies, on the other. Other musical greats, jazz and otherwise, immediately come to mind: Stephen Foster, Bix Beiderbecke, and Charlie Parker. The former two diminished by alcoholism, the latter by drugs and alcoholism. Musicians and artists seem to suffer from other ailments, such as a complete ignorance of financial matters, or, worse, a purposeful neglect of financial affairs. In either case, the behavior is self-destructive, the musical talent and expertise, notwithstanding. The question to be asked is: does greatness, particularly in the musical realm, have to be tinged and singed by self-destructive behavior for the greatness to emerge? Do the two go hand-in-hand?

Please write to me at meiienterprises@aol.com if you have any comments on this or any other of my blogs.

Eugene Marlow, Ph.D.

October 28, 2013

© Eugene Marlow 2013