Some inventions are incremental improvements on pre-existing technologies. Over long periods of time, e.g., tens of thousands of years, the tribal fireplace of yesteryear, for example, bears little technological resemblance to the gas or electric stove of today. Yet, upon even cursory analysis, both technologies provide heat and the ability to cook food. On the other hand, the tribal fireplace also kept predatory animals at bay; the gas or electric stove does not, but the latter stove gives the user much control over the amount of heat required to cook food when it is required. The timeframe between the tribal discovery of the use of fire and the invention of the gas, then the electric stove is at least tens of thousands of years, perhaps a lot more.

Other inventions create tectonic cultural shifts in the human social environment in a much shorter period of time. One such invention is the World Wide Web. Without this technology no one would be reading this blog and I wouldn’t have the opportunity to publish it to be read by a potential international audience.

Sir Timothy John “Tim” Berners-Lee is the British computer scientist best known as the inventor of the World Wide Web. He made a proposal for an information management system in March 1989, and implemented the first successful communication between a Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) client and server via the Internet sometime around mid-November of the same year. The influence of Sir Berners-Lee’s invention is still working its way around the planet. Of course, it should not be forgotten that without the development of the computer—mainframes, mini-frames, and personal—the “mouse,” fiber optics, and a host of other hardware and software developments associated with the computer, the World Wide Web Berners-Lee invented would not have any meaning whatsoever. It is a perfect example that every invention has its antecedents and coincident technologies, just like the fireplace has evolved over time into the gas or electric stove.

Sir Timothy John “Tim” Berners-Lee is the British computer scientist best known as the inventor of the World Wide Web. He made a proposal for an information management system in March 1989, and implemented the first successful communication between a Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) client and server via the Internet sometime around mid-November of the same year. The influence of Sir Berners-Lee’s invention is still working its way around the planet. Of course, it should not be forgotten that without the development of the computer—mainframes, mini-frames, and personal—the “mouse,” fiber optics, and a host of other hardware and software developments associated with the computer, the World Wide Web Berners-Lee invented would not have any meaning whatsoever. It is a perfect example that every invention has its antecedents and coincident technologies, just like the fireplace has evolved over time into the gas or electric stove.

In addition to virtually every aspect of life—marketing, public relations, politics, science, medicine, education, dating, business, music distribution, and many, many more applications—the World Wide Web has had a major impact on journalism. For example, it is a fact that as more and more consumers, especially younger consumers, of news and information gravitated to the web as their primary source, the impact has been greatly felt in the realm of print journalism, especially newspapers. Over one generation the number of newspapers in the United States has diminished steadily. There’s a long list of reasons, too numerous to articulate in this blog. Suffice it to say, the characteristics of the Internet—a 24/7, speed of light medium that incorporates text, graphics, motion video/film, and sound, and the ability to communicate  globally via email—is very attractive to both consumers and marketers alike. I have previously referred to it as the “shrinkwrap medium.” For more details on this, my 1997 book WebVisions (Van Nostrand Reinhold) covers many of the aforementioned issues. Print magazines, broadcast radio and television, and cable television appear to have survived the Internet onslaught—so far.

globally via email—is very attractive to both consumers and marketers alike. I have previously referred to it as the “shrinkwrap medium.” For more details on this, my 1997 book WebVisions (Van Nostrand Reinhold) covers many of the aforementioned issues. Print magazines, broadcast radio and television, and cable television appear to have survived the Internet onslaught—so far.

Clearly, though, the future of journalism is more electronic than print. There is a brief scene in the 2002 Tom Cruise movie “Minority Report” in which the main character, Chief John Anderton, gets off a future style subway. As he does one can see riders reading “newspapers” with pictures that have motion characteristics. Of course, these newspapers are probably made of hybrid materials other than newsprint in order to accommodate the motion graphic elements of news and feature stories and advertising.

This leads logically for a commentary on the emergent field of “multimedia journalism,” a.k.a. “digital journalism.” First, let’s define “multimedia journalism.” According to The Multimedia Journalist: “The most obvious and common definition is the collective use of many media types–such as text, audio, graphics, animation, video, and photographs–to convey information.” (http://www.themultimediajournalist.net/?page_id=330). Again, here we are talking about information in various media conveyed by means of computer-based technology.

This is an ample definition. It squares with the “shrinkwrap” characteristics of the Internet. In other words, the Internet, for journalistic purposes, allows journalists and publishers (and bloggers like myself) to use a multiplicity of media to tell a story; and this can be done 24/7 at the speed of light. While the speed with which stories can be conveyed on the Internet is fraught with its own problems and challenges, what is germane in the context of this blog is the “perceived” difference between “multimedia” or “digital journalism” and what has now become “legacy journalism.”

Remember the fireplace/gas-electric stove analogy at the beginning of this blog? It applies here to the comparison between “multimedia/digital journalism” and “legacy journalism.” Legacy journalism refers, of course, to what came before the World Wide Web evolution: print (newspapers and magazines), photography, broadcast radio, broadcast television, and cable television. All these antecedents to web journalism have been subverted by the growth of the Internet on a global basis—although it must be pointed out, perceptions to the contrary, that a little less than 40% of the world’s population currently has access to the web. Give it another generation, though, and that number will probably double.

It is my view that consumers, journalists, and educators alike are under the impression that somehow “digital journalism” is something new and requires a whole new set of rules and techniques. To a degree this is correct, but it is not the journalism that is new, it is the digital characteristics of the Internet technology that is new. Journalism is still journalism, regardless of the conveyance of the news and/or information. A print story is a still a print story, whether in a “printed” newspaper, or on the newspaper’s web site. A radio news story must still adhere to the demands of news for the ear, whether broadcast via a radio station or network, or on the station or network’s web site. A broadcast or cable news story must still respond to the opportunities provided by these electronic media to incorporate text, sound, graphics, and studio and/or field reporters, live or recorded whether broadcast or distributed on cable, or on a web site.

So what is different? What is different is how the legacy media are programmed into the web, via such programs as WordPress, I-Movie, FinalCut X, GarageBand, and many, many other software programs. What is different is that journalists are now required to not only do the heavy lifting with respect to researching a story, getting interviews, gathering graphics, arranging for and obtaining interviews, and drafting the story—regardless of medium—they now must also train to use a panoply of software programs to post the story on the web.

For seasoned professionals, educators, and journalism students alike this is the new challenge—in addition to learning journalism techniques, everyone must now learn the technology of getting the story (as in using a video camera, for example) and posting a story. In one sense, this is a situation that provides for professional growth. In another sense, it is also an opportunity for the owners of journalistic venues (e.g., publishers) to get more for less. Journalists are increasingly required to know how to make journalism in various media, but this also results in an opportunity for owners to create profits in an increasingly competitive information and news market.

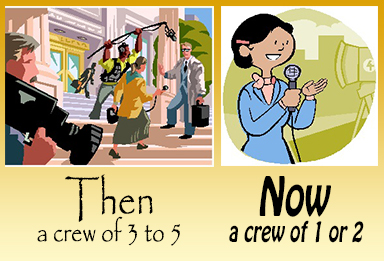

In effect, the growth of the Internet has put more of a professional burden on journalists while at the same time many journalistic functions have been eliminated. One example, before the advent of highly portable, high quality video cameras, broadcast and cable reporters used to have a crew of several members to report a story; similarly with respect to editing.  Now video reporters in many small and medium-sized markets are required to know how to shoot and edit the story themselves without benefit of an experienced crew. The division between reporting and the technology of getting a story to an audience via the web has been greatly blurred.

Now video reporters in many small and medium-sized markets are required to know how to shoot and edit the story themselves without benefit of an experienced crew. The division between reporting and the technology of getting a story to an audience via the web has been greatly blurred.

It is a fact that in the last few years one-fifth of all journalists have been eradicated, one could say purged from the field. Those who remain and those students who are motivated to enter the field face a reality that electronics is the future, although that future will not be as fast in coming as the headlines suggest. It only seems that way. Journalism educators, too, face the same challenge. The problem is learning the new technologies and technical requirements seems to have become the dominant aspect of journalism education, to the detriment of the need to also tell a good story by answering who, what, why, when, where, and how, regardless of medium.

It is a balancing act that requires both experience and technical skill. But what happens when a younger, future generation brought up in a primarily non-print journalism world goes to work or becomes part of the education system whose mission it is to train the next generation of journalists? Will the thousands of years of collective cultural experience telling the stories of the tribe orally, in print, or via video be lost, or will it even matter? Will the knowledge of how to make fire without gas or electricity be forgotten?

Please write to me at meiienterprises@aol.com if you have any comments on this or any other of my blogs.

Eugene Marlow, Ph.D.

January 6, 2014

© Eugene Marlow 2014