There’s been a lot of press recently about the disparity between the rich and the poor on the planet. To wit, the headline reads, “The richest 85 people in the world have as much wealth as the bottom 3.5 billion on the planet.”

The gap between rich and poor story is not new. History relates there has always been a disparity between those at the top of the wealth pyramid and those at the bottom, especially since the development and evolution of writing. In tribal times, where orality was the dominant form of human communication, there is the appearance of more equal distribution of perceived assets, except of course, when it came to the tribal chief whose status demanded greater access to so-called “wealth,” perhaps in the form of more wives or livestock than everyone else.

Regardless, wealth disparity on this planet has been an economic fact of life for thousands of years. But now there seems to be a change. In a recent Q&A on AOL.com, the authors posit:

Q. Hasn’t there always been a wide gulf between the richest people and the poorest?

A. Yes. What’s new is the widening gap between the wealthiest and everyone else. Three decades ago, Americans’ income tended to grow at roughly similar rates, no matter how much you made. But since roughly 1980, income has grown most for the top earners. For the poorest 20 percent of families, it’s dropped. Incomes for the highest-earning 1 percent of Americans soared 31 percent from 2009 through 2012, after adjusting for inflation, according to data compiled by Emmanuel Saez, an economist at University of California, Berkeley. For the rest of us, it inched up an average of 0.4 percent. In 17 of 22 developed countries, income disparity widened in the past two decades, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Enter the Internet

When we talk about the Internet we must be careful to define our terms. The Internet of 1968 as developed by DARPANET (the Department of Defense) is quite a different Internet from the one that followed Sir Timothy Berners-Lee invention of the World Wide Web in 1989. The World Wide Web allowed for the integration of text, graphics, motion film and video, and sound. Many, including myself, envisioned that the Internet of the 1990s would provide a level playing field between the large mercantile organizations and startups and small businesses.

When we talk about the Internet we must be careful to define our terms. The Internet of 1968 as developed by DARPANET (the Department of Defense) is quite a different Internet from the one that followed Sir Timothy Berners-Lee invention of the World Wide Web in 1989. The World Wide Web allowed for the integration of text, graphics, motion film and video, and sound. Many, including myself, envisioned that the Internet of the 1990s would provide a level playing field between the large mercantile organizations and startups and small businesses.

In a very real way, the technological evolution of the Internet and the ability to access software programs and hardware networks (for a modest fee) allowed non-established and non-traditional entrepreneurs to get into the money-making game without the need for large sums of start-up capital. The result is 634 million web sites as of December 2012 according to Yahoo.com. Now anyone on the planet with access to the right software, hardware, and telecommunications network, can set up a web site and be in business.

Yet what has happened since the advent of the Internet as we understand it, post 1989? Media guru Dr. Marshall McLuhan, who wrote Understanding Media: The Extensions  of Man (McGraw-Hill 1964), would not have been surprised to learn that several professions, especially those requiring creative talent and expertise have been devastated by the advent of the Internet, and as a result have made it extremely difficult for those in these professions to make a living, putting them behind the proverbial financial eight-ball. These professions are: musicians, journalists, and photographers.

of Man (McGraw-Hill 1964), would not have been surprised to learn that several professions, especially those requiring creative talent and expertise have been devastated by the advent of the Internet, and as a result have made it extremely difficult for those in these professions to make a living, putting them behind the proverbial financial eight-ball. These professions are: musicians, journalists, and photographers.

When a new technology comes along—such as the Internet—that provides characteristics that heretofore did not exist, or if they did exist weren’t very effective or efficient, that new technology tends to push the older technology out of the way, or at best, the older technology finds a new purpose in life. Two examples: When the telegraph was installed in the western states of the United States, the Pony Express vanished almost overnight. When the Internet came along, while it did not happen overnight, classified advertising pages in virtually every newspaper shrank to almost nothing. It is just easier and cheaper to advertise online than it is to advertise in print.

The Internet has devastated the music, journalism and photography professions. The ability to file share, inaugurated by Netscape, made the principle of intellectual copyright almost obsolete overnight. For musicians, especially, the value of one’s music monetarily speaking has been greatly diminished. CDs sales and radio play used to garner significant income—no longer. Physical CD sales have given way to streaming and downloading. What was once thousands of dollars has devolved into pennies. With the Internet, journalists, cum bloggers, can now create their own publishing space, resulting, in part, in too many would-be journalists saying too many things about everything devolving the value of experienced, professional reporting. Photographers are in the same boat as musicians. Their visual work, if online, is now prey to anyone who can download it. The same is true of written work of any kind if it is online. The potential for plagiarism is rampant. The value of the output of musicians, journalists, and photographers has been diminished in one technological stroke.

Yes, the Internet has leveled the playing field. Perhaps it is more accurate to say the Internet has leveled the players on the playing field. Further, the Internet has provided yet another opportunity for the savvy to accumulate wealth, contributing, perhaps greatly, to the growing income disparity referenced earlier.

Siren Servers

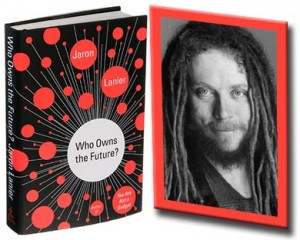

Jaron Lanier in his 2013 book Who Owns The Future? (Simon & Schuster) makes the point that the Internet, rather than providing opportunity for all, has actually created a technological context of “winner take all.” Sound familiar? It is a parallel observation to the fact that in the last thirty years or so fewer and fewer people have accumulated more and more of the planet’s wealth.

Jaron Lanier in his 2013 book Who Owns The Future? (Simon & Schuster) makes the point that the Internet, rather than providing opportunity for all, has actually created a technological context of “winner take all.” Sound familiar? It is a parallel observation to the fact that in the last thirty years or so fewer and fewer people have accumulated more and more of the planet’s wealth.

Here are a few quotes from his book:

At the height of its power, the photography company Kodak employed more than 140,000 people and was worth $28 billion. They even invented the digital camera. But today Kodak is bankrupt, and the new face of digital photography is Instagram. When Instagram was sold to Facebook for a billion dollars in 2012, it employed only thirteen people. (p. 2)

Ordinary people will be unvalued by the new [information] economy, while those closest to the top computers will become hypervaluable. (p. 15)

There’s an old cliché that goes, “If you want to make money in gambling, own a casino.” The new version is “If you want to make money on a network, own the most meta server.” If you own the fastest computers with the most access to everyone’s information, you can just search for money and it will appear. (p. 31)

These quotes are just the tip of the iceberg in a volume full of valid observations. Lanier should know. He is a computer scientist and musician, best known for his work in virtual reality research. Time Magazine named him as one of the “Time 100” in 2010. Lanier and his friends co-created start-ups that are now part of Oracle, Adobe, and Google.

One of his most telling observations is about “siren servers” (or “head end” to use a cable term) and content. And it relates to very recent articles discussing the value of news and information “aggregators”—i.e., web sites that draw content from other sources and “aggregate” them in one  place. And this is the point: some of the most successful web sites on the planet do not create one wit of content; they merely provide an effective and efficient platform for others to provide content that can be shared with other people FOR A FEE, either from the users or from advertisers, or both!

place. And this is the point: some of the most successful web sites on the planet do not create one wit of content; they merely provide an effective and efficient platform for others to provide content that can be shared with other people FOR A FEE, either from the users or from advertisers, or both!

It should not take much thinking to identify these web sites: Facebook, Paypal, Google, Yahoo, e-bay, Twitter, Linked In, as well as the myriad number of crowd funding and fundraising sites, et al. None of these web sites creates one wit of content, yet millions have flocked to these sites with personal and professional information, or product and services for exchange. Regardless of the outcome of the exchange, the web site makes money—lots of it. And those closest to the “siren server” benefit the most.

It cannot be mere coincidence that since the advent of 24/7 cable news in 1980 followed swiftly by interactive cable, then the world wide web in 1989 (the same year as Tiananmen Square), and, in turn, the exponential growth of the Internet that is still in motion to this day, that there has been a staggering, growing disparity between the rich and poor on this planet. Even last week President Obama pointed out that while those at the very top of the economic pyramid have experienced growth in their collective net worths, the middle class has become economically stagnant, and the lower classes have fallen deeper into poverty.

The Internet has not leveled the playing field. It has diminished the value of people and elevated the value of information. It has stunted the mobility of the middle class and pushed the lower classes deeper into an economic black hole. These are the facts. The Internet is the new kid of the technological block and it should come as no surprise that it has created major economic shifts that will play out for some time. When the printing press came along in mid-15th century Europe, enabling the creation of Bibles in the vernacular, it ultimately disrupted the long-held power of the Roman Catholic Church, an effect that is playing out today. There are fewer people attending church services on a regular basis and fewer men and women are seeking the church as a calling.

The Internet has not leveled the playing field. It has diminished the value of people and elevated the value of information. It has stunted the mobility of the middle class and pushed the lower classes deeper into an economic black hole. These are the facts. The Internet is the new kid of the technological block and it should come as no surprise that it has created major economic shifts that will play out for some time. When the printing press came along in mid-15th century Europe, enabling the creation of Bibles in the vernacular, it ultimately disrupted the long-held power of the Roman Catholic Church, an effect that is playing out today. There are fewer people attending church services on a regular basis and fewer men and women are seeking the church as a calling.

The Internet’s force is as powerful as the crushing power of the mile thick sheets of ice during the last ice age. It is inexorable and no government regulation or censorship will stop its inevitable effect. It is much too late to attempt to put the Internet genie back in the bottle. From here on out, the mission is to find ways to use this technology for the larger economic benefit of the population.

Please write to me at meiienterprises@aol.com if you have any comments on this or any other of my blogs.

Eugene Marlow, Ph.D.

February 3, 2014

© Eugene Marlow 2014