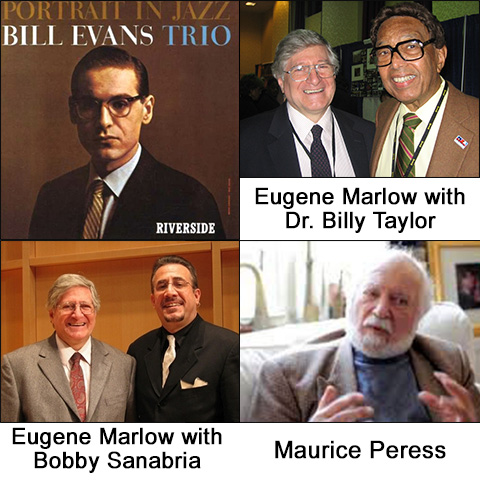

Throughout everyone’s life people cross one’s path who have a significant influence on the course of your personal life and professional pursuits. In a number of Marlowsphere blogs I have already pointed to several people who have influenced my musical pursuits, among them jazz statesman and educator Dr. Billy Taylor, jazz great Bill Evans, and multiple Grammy nominee drummer Bobby Sanabria.

Then there’s Maurice Peress. I was fortunate to have studied with Professor Maurice Peress in 2001. I was re-acquainted with him when I recently attended a talk by Maestro Peress at Bohemian National Hall (321 East 73rd Street in New York City) on “Dvorak to Ellington.” Peress is the author of Dvorak to Duke Ellington: A Conductor Explores America’s Music and Its African American Roots, published in 2004 by Oxford University Press. Peress worked with Ellington in revising the ending of “Black, Brown and Beige,” which he debuted with the American Jazz Orchestra in 1988.

In his talk Peress traced the connection between Antonín Dvorak’s visit to New York City in the 1890s, four of his students  (including among them Will Marion Cook), and the musical careers of Duke Ellington, George Gershwin, and Aaron Copland. It was revealing.

(including among them Will Marion Cook), and the musical careers of Duke Ellington, George Gershwin, and Aaron Copland. It was revealing.

Peress is a man with a very distinguished career. He was selected by Leonard Bernstein as an Assistant conductor with the New York Philharmonic in 1961. Over the next twenty years, he led three American orchestras: Corpus Christi (1962-74), Austin (1970-72) and the Kansas City Philharmonic (1974-80). In 1984 he joined the faculty of the Aaron Copland School of Music and established an MA program for conductors.

In Europe, Peress conducted the Vienna State Opera in the European premiere of Leonard Bernstein’s Mass (1981). More recently Peress worked in the Czech Republic, with the Brno Orkester (1997) conducting Smetana’s epic tone poem Ma Vlast, the FOK Orkester at the Prague Spring Festival (1998) in a Gershwin 100th anniversary concert, the Prague Radio Orkester (1999), and recording music for his TV documentary “Dvorak and America.” In 1999 Peress appeared in London with Jessye Norman and the Barbican Center Orchestra in a tribute to Duke Ellington. In Italy he appeared with the Bregamo/Brescia Festival (1997), the Santa Cecilia Orchestra of Rome (1988) and directed a Gala Gershwin Festival for RIA UNO (2000, Rome Radio TV).

In the Far East, Peress has conducted the Melbourne Symphony (1998), the Shanghai Radio and Television Orchestra (1996-97), the Chunjo and Changjo orchestras (1996) of Korea, and the Hong Kong Philharmonic (1980). He made four tours of China, in 2003-2005 conducting the Shanghai Opera Orchestra, the China National Symphony (Beijing) and the Shenzhen Symphony, where he is Principal Guest Conductor. (Source: http://qcpages.qc.cuny.edu/music/index.php?L=1&M=152)

I studied with Professor Peress at the City University of New York Graduate Center in a doctoral level performance practice course in 2001. It was a small class: four students—two composers, two musicians. From that weekly gathering I produced a paper analyzing Gunther Schuller’s “Third Stream” concept. I also wrote a four-movement piece for violin with piano accompaniment.

What I remember from the weekly sessions was his page-by-page analysis of Leonard Bernstein’s “Mass” and Duke Ellington’s “Black, Brown and Beige.” With respect to the former work I noticed how often Bernstein wrote silent pauses in measures of ¼, that is, a measure of one beat to a quarter note. I had never seen that before. I have since incorporated that approach in both my classical chamber works and jazz compositions for big band. With respect to the latter piece, there was much talk of Ellington’s “blues roots.”

Peress was a formidable presence. Large in frame, but soft in presentation, his voice was clear and strong. His influence on me as a composer is palpable. He nurtured the development of my four-movement violin/piano piece in many ways. For one, I had written a line for the violin that, as he put it, “goes against the instrument.” The line was much too high in register—so much for my attempting to push the envelope, so to speak. From that confrontation I learned it is better to go with an instrument’s comfortable range, rather than attempting to stretch the limits for the sake of “innovation.”

Peress also gently pointed out some holes in my string quartet writing. One piece, in particular, my first string quartet, “Fleur de Neige” (Snow Flower) starts with a solo by the viola, that is, without the other three instruments chiming in. It was a departure from the norm of string quartet composing. But in this instance, Peress was right. The other instruments—the two violins and the cello—needed to have a musical presence while the viola was holding court, so to speak.

Peress also gently pointed out some holes in my string quartet writing. One piece, in particular, my first string quartet, “Fleur de Neige” (Snow Flower) starts with a solo by the viola, that is, without the other three instruments chiming in. It was a departure from the norm of string quartet composing. But in this instance, Peress was right. The other instruments—the two violins and the cello—needed to have a musical presence while the viola was holding court, so to speak.

He also came to my defense with the musicians. In one movement of the violin/piano piece is a section that employs a clear use of jazz chords. The classically trained pianist was confused. Peress got it right away. He explained it to her.

Peress opened my ears to other compositional styles and form. He presented musical material—including Bernstein and Ellington—that broadened my perspective. He influenced my approach to composing. For all of this I am grateful. Thank you Maestro Peress.

If you have any questions or comments about this or any other of my blogs, please write to me at meiienterprises@aol.com.

Eugene Marlow, Ph.D.

November 24, 2014

© Eugene Marlow 2014