Journalism must be doing something right: it is under siege around the world.

Not only is journalism under attack by intellectuals and pundits on the left and the right, it is under attack in the most violent of ways, such as the recent “terrorist” style attack on Charlie Hebdo in Paris, France.

Charlie Hebdo was introduced in 1970 after another publication, Hara-Kiri, was banned for mocking the death of former French President Charles de Gaulle. Much of Hara-Kiri’s staff simply migrated to the new publication, which was named in reference to Charlie Brown comics. Hebdo is short for hebdomadaire which means weekly in French.

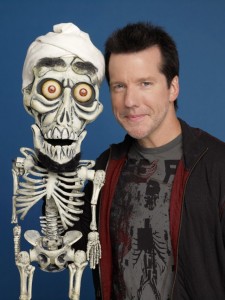

The attack that left 12 people dead—including several cartoonists—is similar in motive to the modus operandi of the extremists in Syria and parts of Iraq. Their view is: “We don’t like what you have to say about our extremists views, therefore we will kill you.” The Boko Haram’s way of doing things—“anything western, especially education, is to be rejected”—is in a similar vein. Their views are so  psychotic and off the chart, they are ripe for ridicule. One such example is ventriloquist Jeff Dunham’s “Achmed, the Dead Terrorist” whose constant refrain—when he doesn’t like the audience’s reactions—is “I kill you.” It is, of course, a hilarious, empty threat. Disturbingly, the Paris killers, the ISIS methodologies, and Boko Haram’s strategies are, collectively, life imitating art.

psychotic and off the chart, they are ripe for ridicule. One such example is ventriloquist Jeff Dunham’s “Achmed, the Dead Terrorist” whose constant refrain—when he doesn’t like the audience’s reactions—is “I kill you.” It is, of course, a hilarious, empty threat. Disturbingly, the Paris killers, the ISIS methodologies, and Boko Haram’s strategies are, collectively, life imitating art.

And these are not isolated instances.

The 2014 World Press Freedom Index “spotlights the negative impact of conflicts on freedom of information and its protagonists. The ranking of some countries has also been affected by a tendency to interpret national security needs in an overly broad and abusive manner to the detriment of the right to inform and be informed. This trend constitutes a growing threat worldwide and is even endangering freedom of information in countries regarded as democracies. Finland tops the index for the fourth year running, closely followed by Netherlands and Norway, like last year. At the other end of the index, the last three positions are again held by Turkmenistan, North Korea and Eritrea, three countries where freedom of information is non-existent. Despite occasional turbulence in the past year, these countries continue to be news and information black holes and living hells for the journalists who inhabit them. This year’s index covers 180 countries (the United States, incidentally, is #46 on the list).”

The map clearly shows where in the world there is the most freedom of information (yellow) and the least (deep red), and everything in between. Unfortunately, there is a lot more deep red than yellow or white.

And then there is the issue of direct violence against journalists—either via incarceration or death. The Committee to Project Journalists (CPJ) reports in its annual analysis:

An unusually high proportion of journalists killed in relation to their work in 2014 were international journalists, as correspondents crossed borders to cover conflict and dangerous situations in the Middle East, Ukraine, and Afghanistan. . . .

Reflecting in part the increasingly volatile nature of conflict zones in which Westerners are often deliberately targeted, nearly one quarter of the journalists killed this year were members of the international press, about double the proportion CPJ has documented in recent years. Over time, according to CPJ research, about nine out of every 10 journalists killed are local people covering local stories.

In total, at least 60 journalists were killed globally in 2014 in relation to their work, compared with 70 who died in 2013. CPJ is investigating the deaths in 2014 of at least 18 more journalists to determine whether they were work-related.

With respect to incarceration, the CPJ reports:

The Committee to Protect Journalists identified 221 journalists in jail around the world in 2014, an increase of 10 from 2013. The tally marks the second-highest number of journalists in jail since CPJ began taking an annual census of imprisoned journalists in 1990, and highlights a resurgence of authoritarian governments in countries such as China, Ethiopia, Burma, and Egypt.

The Committee to Protect Journalists identified 221 journalists in jail around the world in 2014, an increase of 10 from 2013. The tally marks the second-highest number of journalists in jail since CPJ began taking an annual census of imprisoned journalists in 1990, and highlights a resurgence of authoritarian governments in countries such as China, Ethiopia, Burma, and Egypt.

China’s use of anti-state charges and Iran’s revolving door policy in imprisoning reporters, bloggers, editors, and photographers earned the two countries the dubious distinction of being the world’s worst and second worst jailers of journalists, respectively. Together, China and Iran are holding a third of journalists jailed globally—despite speculation that new leaders who took the reins in each country in 2013 might implement liberal reforms.

Despite benign protestations to the contrary, the United States is in the throes of a trend towards restricted freedom of the press—a trend that has been in process for over three decades. There used to be 80 media companies in the United States, however, through acquisition and applied technology there are now less than 10. According to Forbes, these are world’s largest media companies (in rank order):

- COMCAST

- Disney

- Fox

- Time Warner

- Time Warner Cable

- Direct TV

- WPP

- CBS

- Viacom

- DISH Network

The implication is that with this massive media consolidation, the opportunity for independent reporting is shrinking.

Strange. We’re talking about an idea: the concept of freedom of expression. In the context of this blog, this freedom of expression is conveyed through journalism. Yet in too many parts of the world freedom of expression is feared. Is the pen truly mightier than the sword? Keep in mind that such documents as the Magna Carta, the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and the United Nations Charter are just ideas on paper, but they have the power to govern, to give heft to people’s need to express their views without resorting to violence.

Strange. We’re talking about an idea: the concept of freedom of expression. In the context of this blog, this freedom of expression is conveyed through journalism. Yet in too many parts of the world freedom of expression is feared. Is the pen truly mightier than the sword? Keep in mind that such documents as the Magna Carta, the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and the United Nations Charter are just ideas on paper, but they have the power to govern, to give heft to people’s need to express their views without resorting to violence.

The violence against journalism and journalists that has become prevalent globally is an indication of journalism’s strength. If it didn’t have power to persuade and to inform, who would care?

When the Taliban leader in the hills of Afghanistan said recently in a television interview that he and his 150 men would fight democracy wherever they could, did he have any idea what he was saying? Or was he just repeating what he had been told to repeat?

Being told what to do is an easy way out of becoming a full human being. Stepping into that realm of responsibility is a lot scarier. Raising one’s hand gripping a sword to behead a reporter who might say or write something that disagreed with the executioner’s perception of the world is certainly a short-term answer to silencing one’s critics, but if the history of the world is any guide, you cannot silence everyone forever. Many have tried. All have failed.

When will the extremists learn that in today’s world violence only begets more violence. It does not result in a higher standard of living. It does not lead to great art. It does not lead to inventions or technologies that benefit the culture as a whole. All it does is satisfy for a few moments the twisted, psychotic power cravings of a few, angry men hiding behind their beards, their displayed weapons, their masks, their flags, and the convenient misinterpretations of their chosen religious documents.

Je Suis Aussi Charlie.

Eugene Marlow, Ph.D.

January 12, 2015

© Eugene Marlow 2015