The following blog is based on Dr. Eugene Marlow’s talk on the Musical Icons of Marc Chagall presented at the 16th Annual Conference of the Media Ecology Association held June 11-14, 2015 at Metropolitan State University of Denver (Colorado).

During a mid-June 2013 visit to the Palais de Luxembourg, Paris, to view an exhibit of Marc Chagall it became evident within minutes how much Chagall used musical icons in his works. This chance exhibit viewing inspired my desire to compose a suite based on these musical icons.

After returning to New York, I researched Chagall’s life (1887 – 1985) and work and learned that over a 75-year career spanning most of the 20th century, he produced over 10,000 works of art in various media, including lithographs, canvas, water color, postcards, murals, and stained glass windows.

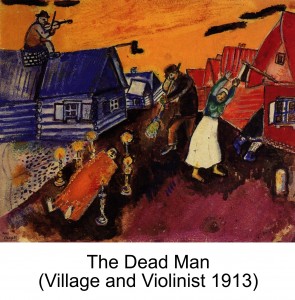

Scholars of his art confirm that Chagall’s use of musical icons is no accident. As a youth in a Russian shtetl consisting of primarily members of religious Jews, Chagall was surrounded by musicians—mostly string players, such as the violin. In his youth, Chagall yearned to learn how to play the violin; his stronger impulse, though, was towards the fine arts.

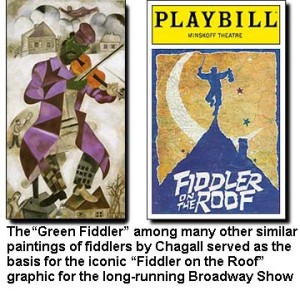

His paintings of violinists, such as “The Seated Violinist” (1908), became the basis for the iconic “Fiddler on the Roof” graphic in the poster advertising the long-running Broadway show of the same name.

His paintings of violinists, such as “The Seated Violinist” (1908), became the basis for the iconic “Fiddler on the Roof” graphic in the poster advertising the long-running Broadway show of the same name.

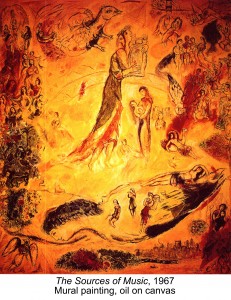

A cursory analysis of several hundred of his artworks reveals 16 different instruments (in alphabetical order): accordion, balalaika, cello, cymbal, flute, guitar, harp, horn, bass drum, keyboard, mandolin, saxophone, small bell, tambourine, trumpet, and violin. Further, there are several graphic references to a full circus orchestra. By far, though, the most frequently “painted” instrument is the violin, followed by the cello, and the horn.

With this “instrumental” record, Chagall, largely, has dictated the instrumentation for my proposed musical work “The Chagall Suite”: (1) violin, (2) cello, (3) double bass, (4) horn (soprano/alto saxophone), (5) flute, (6) trumpet, (7) piano, (8) drums,  and (9) percussion–essentially a string quartet, a woodwind quintet, plus piano and percussion.

and (9) percussion–essentially a string quartet, a woodwind quintet, plus piano and percussion.

Chagall’s work in the 20th century was a time in which classical music evolved out of the Romantic period of the 19th century into the diverse “classical” styles of the 20th century, including serial, minimalist, spectral, postmodernist, and world music, among others. This musical evolution parallels the evolution in art occurring in Europe, especially in Paris where Chagall spent some time in his early youth and later in his life.

Chagall was born in a shtetl in Witebsk, Russia. He studied art in St. Petersberg and went to Paris in 1910. There he rubbed shoulders with some of bright lights of the Paris arts world, including the dancer Nijinsky, the poet Appolinaire, and artist Matisse. His favorite haunt in Paris was the Louvre. From 1914-1922 he was in Russia (he went back to marry Bella, his first wife), where he became the Commissar of Arts in Witebsk after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. In 1923 he resettled in Paris, but following the collapse of France in 1941 he moved to New York City, returning to France in 1948 where he remained until his death in 1985. The city of his birth—Witebsk—is now a city in Belarus following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

There’s much truth in the observation that everything a person does is autobiographical. There’s no escaping it. The way we behave, dress, eat, talk, interact with others, is expressed more often than not as an expression of our inner selves and our experiences. Chagall’s artworks are an outstanding example of this.

Chagall’s iconic themes, of which there are many, include: Jewish life in the shtetl, Christian/Jewish concepts, lovers, the circus, Jewish theatre, the concept of time, street musicians, dancers, acrobats, et al.

Clearly, Chagall is well traveled and you would think his artworks would reflect a broad thematic palette (no pun intended). But it does not. You do not have to look very far to discover what concerned Chagall most in his 98-year life. It can be found in the dedication to his autobiography entitled My Life (Peter Owen Publishers, Great Britain 1965). It was first published in Russia in 1947.

Clearly, Chagall is well traveled and you would think his artworks would reflect a broad thematic palette (no pun intended). But it does not. You do not have to look very far to discover what concerned Chagall most in his 98-year life. It can be found in the dedication to his autobiography entitled My Life (Peter Owen Publishers, Great Britain 1965). It was first published in Russia in 1947.

The dedication reads:

“To my parents, to my wife, to my native town.”

This dedication is especially reflected in the art works that contain musical instruments and/or icons.

And while his My Life autobiography covers a lot of geographical ground, his art works containing musical instruments and icons keep returning to experiences of his early life: his parents and their Jewish life, his first wife Bella, and his native town, Witebsk.

And while musical instrumental icons are present in many of his works, references to them are far and few between in his autobiography. The first reference is as follows:

“Every Saturday Uncle Neuch would put on a tallit, any tallit, and read the Bible aloud. He played the violin, like a cobbler.” (p. 25)

Not very complimentary, to say the least, but in that one short statement you get a sense of his family, the shtetl, and the Jewish life surrounding him.

Later he describes a wedding procession. He states:

“I like wedding musicians, the sounds of their polkas and waltzes.” (p. 35)

Still later, he recounts:

“I had undertaken to help the cantor and, on holy days, the whole synagogue and I could hear the strains of my sonorous soprano distinctly. . . .I’ll be a singer, a cantor, I’ll go to the Conservatory. In our courtyard there also lived a violinist. I did not know where he came from. During the day, he was an ironmonger’s clerk; in the evenings, he taught the violin.” (p. 41).

In a passage in a later chapter he expresses his yearning to expand his personal and professional horizons. He says:

“I do not want to be like all the others; I want to see a new world. In answer, the town seems to snap like strings of a violin, and all the inhabitants begin walking above the earth, leaving their usual places. Familiar figures install themselves on the roofs and settle down there.” (p. 95).

When he returns to Witebsk following his first sojourn in Paris, he describes the place of his birth as follows:

Witebsk is a place apart; a town unlike any other, an unhappy town, a boring town. A town full of girls, who, for lack of time or courage, I never even approached. Dozens, hundreds  of synagogues, butcher’s shops, passersby. Was that Russia? It’s only my town, mine, which I have rediscovered. I come back to it with emotion. (p. 118).

of synagogues, butcher’s shops, passersby. Was that Russia? It’s only my town, mine, which I have rediscovered. I come back to it with emotion. (p. 118).

Witebsk is central to his work. Michael J. Lewis, a professor at Williams College, writing in Commentary, a publication of the American Jewish Committee, makes the following observation:

As cosmopolitan an artist as he would later become, his storehouse of visual imagery would never expand beyond the landscape of his childhood, with its snowy streets, wooden houses, and ubiquitous fiddlers. To fix the scenes of childhood so indelibly in one’s mind, and to invest them with an emotional charge so intense that it could only be discharged obliquely through an obsessive repetition of the same cryptic symbols and ideograms, would seem to require some early trauma. But nothing of the sort is related to Chagall’s copious memoirs, other than his statement that he stuttered. (p. 37).

Not to belabor the point, but it is readily apparent that Chagall’s works reflect his personal and professional life, especially his Jewish life in the shtetl. But his artworks are expressed with an artistic vision and hand that is uniquely Chagall’s. It is like hearing the first few measures of a work by Bach, Mozart, or Beethoven. You know immediately whose hand wrote those notes. The same is true with Chagall. The choice of colors, images, and floating icons is immediately recognizable. And when you discover the plentitude of musical icons in his works you can only conclude that music and musicians were central to his early life, either as a part of his Jewish family upbringing and community culture, or that they appealed to his artistic sensibilities.

If you have any questions or comments about this or any other of my blogs, please write to me at meiienterprises@aol.com.

Eugene Marlow, Ph.D.

June 29, 2015

© Eugene Marlow 2015