Marlowsphere (Blog #148)

The following blog was delivered by Dr. Eugene Marlow on May 1, 2020 to members of the Association of Arts Administration Educators (AAAE) via Zoom for their annual conference.

According to a lyric sung by the late blues singer Alberta Hunter “You cain’t have romance without finance.” The same is true in terms of longevity and survival of profit and non-for-profit organizations. More specifically, arts organizations do not exist for very long without effective financial management and financial support from various external sources.

According to a lyric sung by the late blues singer Alberta Hunter “You cain’t have romance without finance.” The same is true in terms of longevity and survival of profit and non-for-profit organizations. More specifically, arts organizations do not exist for very long without effective financial management and financial support from various external sources.

In the United States government organizations at the national and local level are increasingly withdrawing from the role of funding arts institutions. And applicants for funding are finding it increasingly competitive for whatever funding remains available. Yes, the National Endowment for the Arts budget was increased this year and more foundations are getting into the funding role, but no longer can arts organizations take it for granted that monies will be there.

A case in point: In November 2019 The Turtle Bay Music School, held its final artist series concert, the last hurrah of a nearly century old New York City arts institution. A nonprofit on the East Side that partnered with public schools, the school announced in November 2019 it would be forced to close due to a lack of funding.

A case in point: In November 2019 The Turtle Bay Music School, held its final artist series concert, the last hurrah of a nearly century old New York City arts institution. A nonprofit on the East Side that partnered with public schools, the school announced in November 2019 it would be forced to close due to a lack of funding.

But there is a deeper issue that is pertinent to the training of arts administrators at the graduate level and it is this: if finances and financial administration is the bedrock foundation of an arts organization, how pertinent is the personal financial literacy of those in charge of the organization? My answer is: very pertinent.

Do You Know Your Net Worth?

At the risk of embarrassing myself, I’m willing to bet 80% of the folks in this audience don’t know what their net worth is. You have little idea what your debt-to-income ratio is or how much you’ll need for retirement if you can afford to retire.

My contention is: if you don’t have a handle on your own personal finances, your long-term debt, or how you’re going to finance your retirement, how can you deal effectively and efficiently with the finances of the arts organization you work for or are connected with, or teach students about arts organization financial matters?

It’s Personal

Why am I so keen on this? The answer is simple and personal. My father, Michael Marlow (nee Spivakowsky) , was an excellent  musician: a child prodigy on the violin; Taught himself the viola and the mandolin.; Composed music.; Wrote the world’s first concerto for harmonica and symphony orchestra. It’s still being performed today worldwide.; He had his own radio program on the BBC.; Was a Broadway show conductor.; Performed as a member of the orchestra with many notables, including and Bob Hope and Frank Sinatra. But he was lousy when it came to business and finances. He attempted to build his own music publishing company. It failed. He once dreamed of owning a restaurant. It never happened. When he died at the age of 63 of a second heart attack my sister and I learned he didn’t have any life insurance because he didn’t “believe” in life insurance.

musician: a child prodigy on the violin; Taught himself the viola and the mandolin.; Composed music.; Wrote the world’s first concerto for harmonica and symphony orchestra. It’s still being performed today worldwide.; He had his own radio program on the BBC.; Was a Broadway show conductor.; Performed as a member of the orchestra with many notables, including and Bob Hope and Frank Sinatra. But he was lousy when it came to business and finances. He attempted to build his own music publishing company. It failed. He once dreamed of owning a restaurant. It never happened. When he died at the age of 63 of a second heart attack my sister and I learned he didn’t have any life insurance because he didn’t “believe” in life insurance.

I earned an MBA in part because I didn’t want to put myself in the same financial position my father ended up in. I wanted the vocabulary of business as a means of leveling the playing field professionally.

I’ve been involved in the fine and performing arts in various artistic and management capacities since I was born. At Baruch College (City University of New York) I teach and have taught a panoply of courses in media and culture, and business. At every turn I have experienced and observed that where there is a lack of focus on finances, regardless of the quality of the creativity, the enterprise falters. Further, this failure often, if not always, has roots in a key individual’s lack of understanding or appreciation of personal finances.

Personal Finance vs. Organizational Finance

Aye, there’s the rub. There’s no escaping the connection between personal finances and organizational finances.

What is the difference between personal finance and organizational finances? There are, of course, differences in terms of scale and function, but there is at least one major commonality: assets and liabilities.

In the personal finance context an asset could be liquid assets, et al. In the corporate context an asset could be liquid assets, etc. In the personal finance context a liability could be a long-term debt. In the corporate context a liability could also be long-term debt.

In other words, the difference between the personal finance context and the corporate context is scale and function.

Financial Literacy

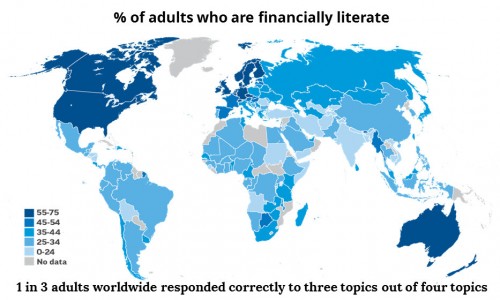

This all relates to a much larger context and that is global financial literacy. According to a 2014 Financial Literacy Around the World: Insights From The Standard & Poor’s  Ratings Services Global Financial Literacy Survey:

Ratings Services Global Financial Literacy Survey:

Worldwide, just 1-in-3 adults show an understanding of basic financial concepts. Although financial literacy is higher among the wealthy, well educated, and those who use financial services, it is clear that billions of people are unprepared to deal with rapid changes in the financial landscape. Credit products, many of which carry high interest rates and complex terms, are becoming more readily available. Governments are pushing to increase financial inclusion by boosting access to bank accounts and other financial services but, unless people have the necessary financial skills, these opportunities can easily lead to high debt, mortgage defaults, or insolvency. This is especially true for women, the poor, and the less educated—all of whom suffer from low financial literacy and are frequently the target of government programs to expand financial inclusion.

Further, in the United States, according to this same survey, the financial literacy rate is only 57%. Denmark and Sweden have the highest financial literacy rates at 71%.

In 2019, Investment News reports on an updated Standard & Poor’s survey, as follows:

Although the U.S. is the world’s largest economy, the Standard & Poor’s Global Financial Literacy Survey ranks it No. 14 (tied with Switzerland) when measuring the proportion of adults in the country who are financially literate. To put that into perspective: the U.S. adult financial literacy level, at 57%, is only slightly higher than that of Botswana, whose economy is 1,127% smaller.

Although the U.S. is the world’s largest economy, the Standard & Poor’s Global Financial Literacy Survey ranks it No. 14 (tied with Switzerland) when measuring the proportion of adults in the country who are financially literate. To put that into perspective: the U.S. adult financial literacy level, at 57%, is only slightly higher than that of Botswana, whose economy is 1,127% smaller.

According to a 2019 report from the U.S. Department of Treasury entitled Best Practices of Financial Literacy and Education at Institutions of Higher Learning:

With the cost of college rising faster than incomes and a staggering 44 million Americans owing more than $1.5 trillion in student loans, there has been growing concern that students and their families are taking on debt without truly understanding the long-term impact.

Indeed, there is a lot of research exploring this national problem: Nine out of 10 parents and students failed a 2018 quiz about student loan debt. Meanwhile, MarketWatch reported that half of college students taking an AIG survey on personal finance basics got two or fewer questions correct. And in a recent survey from the Brookings Institution, less than 30% of student respondents could correctly answer three questions on inflation, interest and risk diversification.

We must conclude then that to insure student success in arts administration programs as educators we must be certain that these same students are financially literate on a personal level, particularly so because as arts administrators the finances of an arts institution is a vital aspect of the institution’s credibility, viability, and longevity.

The Financial Literacy of the Arts Administrator

To put this another way, if an arts administrator isn’t paying attention to his/her personal finances and doesn’t have a firm grip on his/her net worth assets and liabilities, it  would follow that this same arts administrator is not paying enough attention to the institution’s assets and liabilities?

would follow that this same arts administrator is not paying enough attention to the institution’s assets and liabilities?

Now, perhaps this parallelism is not valid. Perhaps the arts administrator is fluent in the institution’s finances and knows the institution’s balance sheet, cash flow, assets and liabilities in great detail. But let’s say this same arts administrator accrues excessive credit card debt, or purchases real estate at the height of a market with a net income to long-term debt ratio that is out of balance and disproportionate. What does this say about this arts administrator’s expertise and skill to manage the institution’s finances? It does not speak well.

The importance of financial issues to arts administrators is nowhere more articulately stated than in the Association of Arts Administration Educators (AAAE) Standards for Arts Administration Graduate Program Curricula of November 2014. The opening paragraphs of the “Financial Management” section of the document states:

Financial management is a core function within the management of cultural organizations, and is the framework through which resources–human, physical and financial—are maintained and monitored. In the not-for-profit sector, the balance between mission and money is a key factor in maintaining a sustainable, vibrant and successful organization, and needs to be clearly understood by arts administration students. We recognize that some programs include the teaching of commercial enterprise in the arts; this version of the standards has not yet incorporated standards for those areas of practice.

The document goes on to describe what arts administration students should be able to do with regard to financial matters at the foundational and best practices levels.

The Financial Literacy of Arts Administration Students

The question is: even though students at the undergraduate and graduate level might be adept at dealing with financial matters in the corporate context in the classroom,  might not their understanding and appreciation of fiduciary functions have deeper meaning if their own personal finances are in order?

might not their understanding and appreciation of fiduciary functions have deeper meaning if their own personal finances are in order?

How many students come into an arts administration program with a foundation in either personal or corporate finance? Textbook learning is not as valuable and purposeful as real life learning. It’s one thing to require students to take a course in corporate finance, but it is quite another if students have no real-life background in finance, personal or otherwise. Students might take a corporate finance course and achieve a high grade, but what is this grade based on? An ability to read and abstract financial content from a textbook and feedback on a test, or is the good grade based on a student’s deeper understanding of finances based on “personal” financial experience?

Possible Prescriptions

A possible prescription for this “in the closet issue” is to provide students with a one credit course in personal finance. It does not have to be complex. But its main objective would be to sensitize students to personal financial matters as part of the process and preparation for dealing with institutional financial matters.

Another solution is to infuse non-financial courses with references to financial matters wherever possible. By doing so, students can begin to relate “personal financial” issues to non-financial course content. Over time, perhaps, students will begin to integrate the “personal” with the “organizational” to everyone’s mutual benefit.

Another solution is to infuse non-financial courses with references to financial matters wherever possible. By doing so, students can begin to relate “personal financial” issues to non-financial course content. Over time, perhaps, students will begin to integrate the “personal” with the “organizational” to everyone’s mutual benefit.

In other words, to borrow and skew a well-worn phrase, charity begins at home. I’m willing to bet that if an arts administrator has a firm handle on his or her own personal finances, the chances are high this same arts administrator is well informed and in control of the institution’s finances. One context informs the other.

It makes sense to me that the more informed an arts administrator is about their own personal finances, the more sensitized this same arts administrator will be to the institution’s finances. You can attempt to bifurcate the two contexts, but if one bar is lower than the other, ultimately one will suffer. Attempting to parse these contexts can lead to problems. Is it not a better idea to prepare an arts administrator student with a solid foundation how to deal with personal finances so that this same student can approach the institution’s finances with the same kind of rigor?

© Eugene Marlow, PhD, MBA 2020